India and Southeast Asia are home to the endangered Asian elephant, which is rapidly declining in numbers due to poaching and habitat destruction.

In Myanmar, there are currently around 5,000 wild elephants, and another 3,500 that have worked in the logging industry carrying timber – an activity prohibited under new legislation. Eight of these ‘unemployed’ elephants are now cared for by Green Hill Valley, a local park on a mission to educate residents and visitors, while providing the elephants with vital veterinary care. Willem Schaftenaar, Veterinary Advisor to the Elephant Taxon Advisory Group, has assisted this project, recently running a workshop teaching regional vets how to use point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) to monitor elephants in the wild, in captivity and at sanctuaries.

I have worked with animals – including elephants – for many years, promoting their health and wellbeing, and am heavily involved in various outreach projects across the world. I recently ran a workshop, along with colleagues from the Vietnam Elephant Initiative, which was extremely successful, attracting participants from Indonesia, Nepal, Thailand, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, India and, of course, Myanmar. The aim of the project was to share our knowledge of elephant medicine and techniques, such as POCUS, that are not readily accessible in these countries, showing participants what is possible with ultrasound technology.

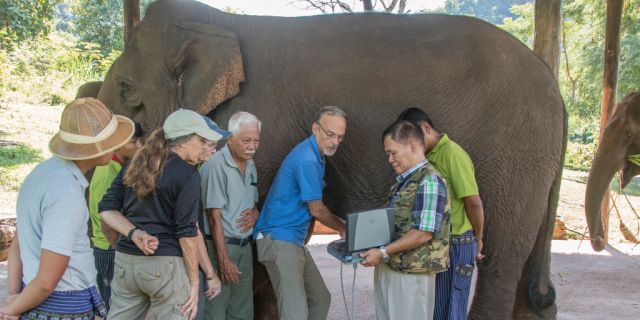

The workshop provided a platform for my colleagues and the 21 participants – elephant keepers, or ‘mahouts’, and vets – who all work with wild, rescued or captive elephants, to discuss ideas and experiences. We brought along a Fujiflim Sonosite ultrasound system so that people could get hands-on experience as we explained the various uses of ultrasound in elephant medicine.

The portable nature of the Sonosite system makes it possible to run these interactive workshops, and the participants were extremely excited to get involved and have a go at ultrasound scanning. One of the benefits of running sessions such as this is that it provides an opportunity for people to ask questions. For example, a participant asked where the best place is to inject an elephant, which gave us a chance to demonstrate how to use the ultrasound system to check the thickness of the skin at various places. The camp gave us access to eight elephants – who were all treated with care and positive reinforcement – that we could use for demonstrations.

Everyone took turns to try out the machine and they were all very impressed with the intuitive nature of the system, and the versatility of its applications. Ultrasound is amazing for general monitoring of elephants and the robust nature of the Sonosite system makes it perfect for using around such large animals! Injuries – the majority of which are caused by poachers – can be assessed at the roadside in the wild, and if the elephant has been shot, tracks from the bullets can be traced. We demonstrated this on an elephant with a 12-year-old gunshot injury to show how ultrasound can be used to locate the bullet, allowing accurate flushing of the wound to prevent life-threatening infection taking hold.

Another elephant that we assessed at the workshop had been attacked by a wild male elephant, or ‘bull’, many years ago and has had a large swelling on its side ever since. Using ultrasound, within a minute we had identified that the elephant had a hernia – characterised by the intestines being directly under the skin – something the mahout had not been aware of for 10 years! Once a problem has been diagnosed, you can check whether there is any clinical discomfort and if treatment is necessary, and determine if there is any immediate health risk. This could have a tremendous impact on the care of injured wild elephants, allowing you to decide when to take action.

One of the main uses of ultrasound is for reproductive assessment. In Myanmar, there are restrictions to prevent elephants being used for work until they are 17 years old and, if they were to get pregnant, they cannot return to work for 5 years. In the logging industry, many female elephants, or ‘cows’, have their pregnancy delayed so that they can work for longer. This means that they may be over 20 years old before pregnancy occurs, which can lead to complications. Using ultrasound, you can monitor the pregnancy throughout and detect when the cow is going into labour, allowing you to anticipate and address any complications as they arise.

By monitoring the cows, and their fertility levels and reproductive cycles from weekly blood tests, we can predict the best time for mating in an attempt to boost elephant numbers in the future. It is also possible to assess the reproductive capacity of bulls by looking at their secondary reproductive organs. This could have a huge positive impact on preventing the Asian elephant from becoming extinct.

Our participants came into the workshop with no knowledge of ultrasound equipment and got the opportunity to learn about its use and test the system first-hand. The success of the course this time round has led to us being invited to host a similar workshop in India, where they are planning to open a new mobile elephant clinic and believe POCUS will be a huge asset to their work.

I am so grateful to the camp for hosting us, and for the invaluable Sonosite system, the portability of which made it possible for us to bring the equipment to Myanmar and show the potential benefits of ultrasound for the health and future life of elephants in India and Southeast Asia.

Learn More About Sonosite Ultrasound for Veterinary Use

A veterinarian’s day can be unpredictable and so are their patients. Discover Sonosite ultrasound systems, the most durable, reliable, portable, and easy-to-use veterinary ultrasound machines available.